.jpg)

When it comes to the discussion on establishing safer prescribing practices among members of the medical community, one group that often is omitted from that conversation is dentists.

However, dental professionals in New Jersey have taken a proactive approach in helping to address the opioid epidemic.

Last fall, the New Jersey Dental Association (NJDA) released guidelines to its members on safe prescribing and dosing of prescription opioids. The NJDA also was proactive in promoting dialogue between dentists and their patients on the addictive nature of opioids and possible alternatives that exist for treating pain.

Further efforts are on the horizon, as the Partnership for a Drug-Free New Jersey is planning a Do No Harm Symposium for dental professionals sometime this fall.

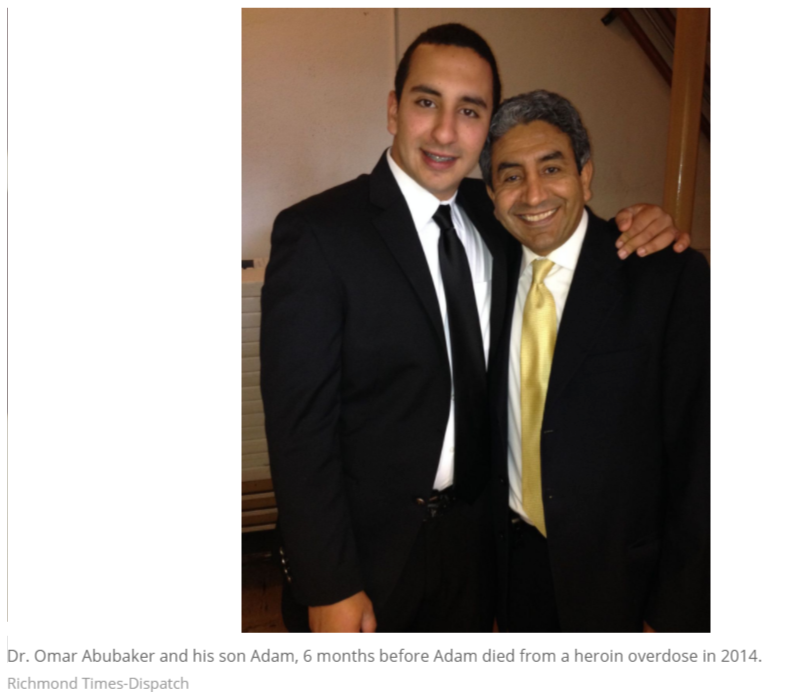

The article below, which appeared in The Roanoke Times earlier this month details how the attitudes on prescribing of a dental professor at Virginia Commonwealth University changed following the overdose death of his 21-year-old son in 2014.

“This is the only disease created by doctors,” said Dr. Omar Abubaker told the publication. “And it could be fixed by doctors.”

From roanoke.com:

VCU professor who lost son to overdose aims to change opioid prescribing practices

A picture in VCU Health’s ambulatory center downtown looks, from a distance, like a tree.

“But if you get closer,” said Dr. Omar Abubaker, “you see it’s actually a collection of faces and images. To me, the opioid epidemic, both to clinicians and to the public, it’s from a distance. If I say, ‘Opioid epidemic,’ the first thing you think about are the graphs, the number of people that died, the statistics.

“For those of us that are affected, it’s about faces, memories, sons and daughters.”

Abubaker is the chair of Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of Dentistry’s Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. He has been with the school for more than 25 years and, for most of his career, he was like every other doctor when it came to prescribing opioids: It was a habit.

But all that changed in September 2014, when his son died of an overdose of heroin, an illicit opioid drug.

The experience radically shifted not just Abubaker’s personal life, but his professional one, too.

Suddenly, he wasn’t seeing the opioid epidemic in terms of charts and graphs and startlingly large annual death numbers, including 1,133 in Virginia last year. He was seeing his 21-year-old son.

And he knows — probably as well as anyone — how providers’ prescribing practices have fed the opioid epidemic. Though he isn’t certain what caused his son, Adam, to use heroin, he does know he was probably over-prescribed opioid painkillers following surgeries when he was a teenager — the same drugs that Abubaker used to frequently prescribe.

“Both in medicine and dentistry, the Hippocratic Oath says, ‘Do no harm,’ ” Abubaker said. ‘In fact, ‘Do no harm,’ comes even before, ‘Do good.’

“So the ‘Do no harm’ part comes down to how we stop prescribing medications as much as we have in the past.

“And the ‘Do good,’ is to see if our society — or any of us — can do something to make this better, to help the families affected.”

Providers have already started changing their prescribing practices, with federal data showing a dip in the most popular painkillers beginning around 2013 in Virginia. The state is also beginning to see fewer prescription painkiller deaths. In the first quarter of 2017, 113 people died from prescription opioids, down from 124 who had died at the same time last year.

But people cut off from the painkillers they grew addicted to have turned to illegal versions of the same basic drug in the form of heroin and fentanyl, offsetting any progress made on the prescription side. There were 127 heroin overdose fatalities so far this year, compared with 110 last year. The deadlier drug fentanyl is killing even more people — 190 so far this year, compared with 145 this time last year.

“This is the only disease created by doctors,” Abubaker said. “And it could be fixed by doctors.”

After the death of his son, Abubaker spent a year educating himself about addiction and received a graduate certificate in international addiction studies.

“I educated myself, because I didn’t want to be talking about it emotionally as a parent. As an educator, I have to talk intelligently and scientifically,” he said.

Dentists in the community still over-prescribe opioids, he said. But he also has hope that, slowly but surely, more dentists are learning about the harm of such prescribing practices. He speaks regularly to community dentists about how they should change their prescribing practices.

When Abubaker was a dental student in the 1980s, opioids weren’t quite as popular. They really began taking off in the 1990s.

“That’s when teaching pain management changed, by pharmacy companies, by hospitals, by everybody that wanted to make sure you gave enough pain medications,” he said. “I vividly remember people telling me that people don’t get addicted if they have pain.

Prescribing opioids became a habit for physicians. And it was the same for Abubaker before his son died. He was a typical doctor, he said, and that meant he would give out prescriptions for pain. He, like most other doctors, didn’t think there was anything wrong with it.

“Before, (it wasn’t) even a thought to give a prescription for a narcotic. It’s just a practice. It’s a habit,” he said. “Everybody that gets a tooth pulled — whether it’s one tooth or 10 teeth or all teeth — they get a prescription. And I don’t want to say I was careless, but I was like 95 percent of doctors and oral surgeons.

“So what I tell you about me before is reflective of the dental profession in general, and the practice of medicine.”

Though the opioid epidemic has been raging for years, Abubaker said dentists continue to over-prescribe opioids.

For the majority of adolescents, dental procedures are the primary way through which they first take an opioid painkiller, he said. Common procedures like wisdom teeth removal often result in such a prescription.

One of the biggest ways to change how opioids are prescribed is simply to inform students of how dangerous they can be, and to train them according to new guidelines developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Virginia Board of Medicine.

Since the School of Dentistry changed the way it teaches about opioids, the school has seen a difference in the number prescribed.

In 2015, 50 percent of the patients who had procedures like extraction or implants at VCU’s Oral and Maxillofacial program received narcotics — a class of drug that includes opioids — according to Abubaker. That is typically a higher number because those patients are more likely to have major surgery. Abubaker said he hopes to lower the rate of patients who receive opioid prescriptions after extractions to less than 10 percent.

Dr. Alan Dow, assistant vice president of health sciences for interprofessional education and collaborative care, said VCU’s medical school has started training its students to prescribe opioids according to the CDC’s safe opiate prescribing guidelines.

Those guidelines state that non-opioid painkillers are preferred, and providers should choose opioids only if the benefit outweighs the risk, the provider has developed a treatment plan with the patient, and they start with the lowest possible dose.

VCU also launched a continuing education program for practicing providers in April at www.safeopiateprescribing.org.

But changing the practices that many doctors have held for decades will not happen overnight.

When one of his children had a medical issue, Abubaker would typically refer them to one of his colleagues. But when he found out his son was battling addiction at the end of 2013, there was no one to turn to.